It was just another flock of pigeons whirling around in their usual sloppy formation above Centre Street in West Roxbury on a Friday morning, a common sight in the city or maybe in most of the civilized world. The kind of thing that draws little notice, nothing like those murmurations of starlings one sees in the videos or in person if one is especially lucky and paying attention. Except for some reason this particular commonplace helter skelter sky collection struck me as particularly beautiful, as I sat in the car ready to show up for yet another eye appointment.

There is actually no mystery in my reaction, here. The threat of loss, especially when it’s something as precious as eyesight, can add an emotional boost and a heightened level of appreciation for any aspect of living. It is a cliché to say that humans tend to take way too much for granted, and also somewhat true that the more stable and steady and trauma-free one’s life has been, the greater this is likely to be. This is especially true for those of us whose existence benefits from the stability and wealth found in the richer countries of the world, and not true at all for the victims of grinding poverty or war or political upheaval or earthly disasters, such as hurricanes or earthquakes or drought, that are a way of life in so much of the rest of it. Which isn’t to say that misfortune and loss can’t be found in all societies and places, rich and poor. Such stories are a big part of what is known as “the news”.

It should be no secret to you that unexpected upheaval – call it trauma – can show up in any life at any time anywhere you care to look. Live long enough and chances are you will encounter the loss of someone you love, because life on this planet is mortal. Events like fires and car crashes or accidents of any kind can generate trauma that lasts a lifetime in the memory, where the goal is to heal as much as one can. Some succeed at this better than others. This kind of story is familiar to all of us, though the luckier among us know it mostly through books and movies and stories we’ve heard somewhere about somebody else.

But not all trauma is the stuff of high drama and horrific moments. There are those traumas that are almost low key in comparison, taking place over time in a kinder and gentler way in what is an ongoing progression of disturbing events. With these the trauma plays out in a more subtle and long-lasting way, whereby the threat of total catastrophe never gets realized but also never quite goes away, nor does the potential for bonafide catastrophe at some indeterminate point in the future. Call it the trauma that keeps on giving.

I have had regular eye appointments – the serious kind, with an ophthalmologist whose thing is pathology, as opposed to your friendly optometrist who provides your eyeglasses or contact lenses – for over twenty years, and a regular part of the lead-up to every one of these has been a few or more than a few anxious moments. Then the appointment takes place, and for a long time now the results have been more or less benign, at which point the premonitions of catastrophe disappear for awhile – until the next appointment rolls around. In good times these endless rendezvous happen every four or six months. In darker times it’s been more like every month or two, or several per month, and back in the truly dark early times a few could happen in a single week, when the anxiety was kind of off the charts, as one might expect. And therein lies a tale, which I tend to think about very little until the inevitable next event appears on the calendar, like it did the Friday before Christmas, when I was impressed at the wondrous sight of those circling pigeons.

This tale is now twenty years long and counting, and this writer is well aware of how old people are infamous for obsessing about their medical problems, usually to the interest of nobody except other gracefully aging folk waiting to tell their stories. With these facts in mind, we shall stick to the highlights, which also tended to be very low moments:

- It started with a puff test at the eye glass place. Most of us are familiar with these; they are a somewhat “quick and dirty” test for glaucoma, not definitive but indicative of possible trouble. For most a puff test is an odd and startling annoyance that precedes moving on to the nitty gritty of getting the glasses. Which had been the case with me for thirty years until one day it wasn’t, and I was told to get that other kind of eye appointment, the sooner the better.

- That happened at my regular doctor’s office with their monthly visiting ophthalmologist, who used a better device for measuring eye pressure which offered a very sobering result: whereas as “normal” eye pressure is generally considered to be 10-21mm Hg, she was getting something like 37 in the right eye. The left was normal. She asked if I’d noticed any odd features in my vision, like haloes around streetlights. Why yes, I’d been seeing these for months, so?

- She gave me a brief introduction to the basics of glaucoma, how it mostly involves high ocular pressure which unfortunately gradually destroys the optic nerve and how more unfortunately any losses are irreversible, and how I’d likely been losing vision for many months. “Thirty seven” I think I remember her telling me “is really high”. Call that the first traumatic moment. She told me I needed something drastic like laser surgery straight away, and it’s possible she made a phone call and set up an appointment with a guy who had the equipment at a nearby hospital, probably the next day or maybe even that very afternoon. Traumatic moments tend to blot out lesser details of the remembrance, so let’s just say the surgery happened in short order.

- The guy did his tests and did the surgery, which was quite straightforward, though his instruction to “sit very still” while he shot a hole in the back of my eye with his laser was somewhat traumatic, as one might expect. Or so this layperson has always assumed is what happened. The point was to create a drain for the optic fluid, so as to relieve the pressure, though this simplified plumbing assessment might be way off and I don’t care. It didn’t hurt and he gave me various drops to use and to come back in a week.

- The return visit confirmed success and the left eye was still fine so premonitions of blindness were kept in check, at least for the moment. Again the details are hazy but I think I was to take the drops and return for weekly or biweekly appointments for awhile. I was relieved and not all that anxious anymore, and had only the vaguest notion that the right eye had lost vision, but now that it had been mentioned, I could swear things were a bit darker in that right eye compared to the left.

- At some point two things happened: the left eye developed glaucoma (“this is usually what happens” said my guy) and pressure rose in the right eye once again. The traumatic effect of this matched that first state of shock, and imaginings about living out life as a blind person became overwhelming, at times. Of course, unlike sudden and violent catastrophe such as a car crash or heart attack or falling off a bridge, this one was playing out slowly, and the ultimate consequences were anything but clear. A good thing in some ways, but bad insofar as it offered much fodder and plenty of time for the imagination to conjure whatever terrors might come to mind. Such is the basic wiring of the human brain, and some of us are better at terrorizing ourselves than others.

- Over the course of the next year, both eyes received their share of laser treatments. These worked for awhile, until they didn’t, so various eyedrop medications were tried. These worked for awhile until the right eye was not responding to anything. I had fantasies about how lots of people manage fine with one good eye, like pirates and Wiley Post, a hero-aviator from the 1930s. However, the general trajectory of this whole experience seemed to be a kind of gradual free fall with only very undesirable consequences down there at rock bottom, if things fell all the way. Of course, I wasn’t going to be dead or anything, but is it not understandable that in the depths of this experience that felt like a very small consolation? Trauma in the moment tends to not lead to sober rational thinking or anything like gratitude for what one has; you’d know this if you’ve ever been there, though of course I may be speaking only for myself.

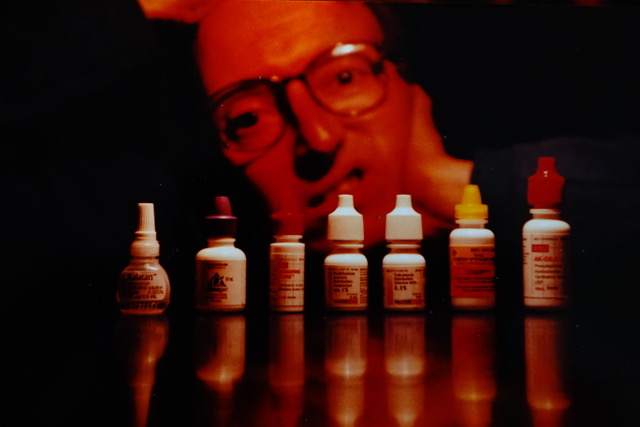

- What happened next was a kind of “to the mattresses” strategy, which is what they said in Godfather I and what it means is resorting to extreme measures, which in this case one might call a trabeculectomy. This is not a laser procedure but a one hour process in an operating room whereby the surgeon pokes around cleverly (with sharp instruments I imagine but don’t really care to know more) so as to create a more elaborate structure for lowering eye pressure than lesser methods can achieve. My guy called it a “bleb” which sounds like something from a cartoon or a scrabble dictionary, and he was quite happy with how it went. Post-op required an awesome array of eye drops, to be applied on a somewhat complicated schedule. The pictures offer a good perspective on this.

- Post-op was painless but also traumatic, as measuring the pressure the next week, what they got was zero. Nada. No pressure at all. The Dylan line came to mind: “where black is the color and none is the number”, though Bob had likely not written that song with my situation in mind. though it did kind of feel like a hard rain was falling in my life at the moment. On the other hand, one might ask whether this result in the pursuit of lower eye pressure simply denotes fabulous success . As you might have guessed, the answer is no, and as you might have also guessed there’s got to be some kind of pressure to allow the eye to maintain its shape or whatever. You might’ve also read somewhere that 10 mm Hg is considered the bottom range of “normal”, for whatever reasons. Which were probably explained to me but the overwhelming feelings of catastrophe returned – can the eyeball just sort of collapse in on itself? Where was this roller coaster rolling next? I should also add that visual acuity in this eye had gone from kind of fuzzy to truly and completely blurry.

- What ensued was another hurried visit to yet another eye doctor downtown, a specialist in these matters. Living in the medical hub of the universe has its good side, and my guy had his own network of people in the area, many at Massachusetts Eye and Ear, founded in 1824 and a world renowned institution in a city with more than its share of those. I had already been to a few glaucoma specialists there, as my guy, great ophthalmologist that he is, is not a specialist in that particular pathology. I am grateful for his humility. The positive upshot here is that this man who evidently knew his way around low-pressure events said not to worry, and also that “that bleb, by the way, is beautiful”. Which was thrilling to hear in an odd way, and how many of us can brag about our fabulous bleb? The pressure rose over the next few weeks, and in the ensuing years has never made it to 10 but kind of hovered between three and seven and no catastrophic events have ensued over all this time, at least not yet. A common occurrence on many of my eye appointments has been for the tech to do the glaucoma test, look puzzled when they check the right eye, and then proceed to do it again two or three more times, as it seems they cannot believe the reading they’re getting. “Ha ha” I say to myself, not at all bitterly, or at least not for a long time now.

Not for a long time now because after all the uncertainty and sporadic unnerving surprises of those first years, things really did sort of settle out. The introduction of state-of-the-art eyedrops that came along was a turning point, for the longstanding pattern had been for eyedrops to remain effective at controlling pressures for a few months or a year, until they didn’t work anymore, leading to a scramble to find the next one that would help stave off vision loss, or as my mind would tell it, “blindness”. The anxiety, which could sometimes be edged with hysteria, would subside and then rise again as each eye appointment arrived on the calendar, on a roller coaster of its own. I am still riding that one, though now it’s more like one of those low key kiddie roller coasters like you see at traveling carnivals and not the Superman/Space Mountain trip it once was. And of course, as an army of ophthalmologists (maybe not an army but more like a platoon) has told me ad nauseam, “glaucoma is an unpredictable condition”, and more than a few times I’ve received contradictory predictions from so-called “experts in the field”. So it looks like this boy has a lifetime ticket on this ride. “Get over it”, he tells himself, even though he knows it doesn’t work like that.

The saving grace here (there may be many of these that I overlook in my ingratitude) is that vision in my left eye remains more or less normal, as does life with these eyes overall, at least the part for which they are responsible. I read. I drive. I ride my bike in the same hairy traffic situations I always have; there may be more close calls but the funny (and dangerous) thing about close calls is that one is unaware of most of them. The daily fact of life is that I still savor all the visual pleasures that life affords, like always. Of course the right eye offers nothing but a somewhat faded and blurry – let’s call it “impressionistic” – opening on the universe, but it is enough to offer a bit of depth perception and a clear general sense of what is happening with things over to the right, especially anything in motion, such as a leaping tiger or oncoming truck. Information like this helps to keep one alive and I am grateful for that. If I want a clear sense of the vision loss this eye has suffered – probably most of it in that year before this story began – I can look at the results from formal field vision tests, of which I’ve had a great many over the years, or I need merely stare up at the ceiling fan above our bed, which has five blades. If I close my left eye, the two right-hand blades disappear, as if by magic. But of course it’s not magic but merely biology and pathology, or maybe biological pathological magic. Black magic.

Of course as we all grow old gracefully together the odds increase that my story could become your story one of these days – we’re talking biology here. You may in fact already have your own story to share regarding these matters. So many eye pathologies, so many possible catastrophes! So much potential blindness, or something like it. Besides glaucoma there can be retinal issues – tears and diabetic retinopathy – and macular degeneration and cataracts and many lesser ones known best to medical students. My eye guy says a number of these are age related, and the aging population is generating much growth in the field, as there is money to be had. He tells me my cherished eyedrops with their ongoing effectiveness in treating glaucoma are a result of this. New money went into research because it finally looked like a good business plan. Perhaps I’m being too cynical; the fact is I am also most grateful. Thanks, free enterprise!

And of course, if eye pathology can by any measure be seen as benign, the fact is it usually doesn’t kill you. Unless of course it’s something like eye cancer or anything like that. Getting that diagnosis, as we all know, can mean a quick and tragic ending, often as not. But as medical science advances, many lethal maladies once associated with that condition now include a number that can play out over many years with the patient surviving, sometimes for a good part of a “normal” lifespan. Probably the best known of these is breast cancer, that can often be treated successfully if the right circumstances prevail, though for the lucky survivors that is often only the beginning. Chances are you already know this, either from personal experience or knowing someone who has lived it – year after year of annual checkups and tests comes with the territory, and what one is about to discover with each new appointment has the potential to be a life-threatening condition that one just might not survive this time around. What must that be like, in the days or weeks preceding each new clinic event?

Friedrich Nietzsche, the German philosopher, made his grandest contribution to pop philosophy (if there is such a thing) when he tossed out an aphorism that more or less translates as “out of life’s school of war, that which doesn’t kill me makes me stronger”. This has been wildly misquoted and probably misinterpreted over the years, can be seen on T-shirts and heard in movie scripts and chances are you know it so do you remember where you first heard it? In the context of your own long and contemplative life, what would you say it means? I am sure I once had a simple answer for this, one that has been amended some after living with various fears and fantasies about living with blindness, realistic or not. Whether the resultant suffering was needless or unnecessary is beside the point, for the fact is it was real, and it is ongoing. Is there anything of value in this experience, at all? Has it made me stronger in any way that matters?

A couple of things: I have a new appreciation, call it admiration, for all those people living with those worst kinds of medical uncertainty, of which they get reminded every so often year after year, a task they must continually face with courage and grace. For those coping with conditions like cancer or anything truly life threatening, this appreciation rises to a whole new level. I might’ve not walked a mile in their shoes, but I’ve now been a few hundred yards down that road and have some sense of what it is like. The other, of course, has to do with those pigeons. We all take the miracle of life and its many blessings for granted most of the time, as far as I can tell, that’s just how it is. The blessings of the senses, of hearing and sight and touch and smell and however we get to know the world, are up there with the best of what life offers. It is probably well and proper that we rarely if ever think about being grateful for these things, or even for life itself; what matters far more is that you live it. I can only imagine how those who’ve faced death and avoided it, those who get reminded of this with every new oncology appointment, must have a special appreciation for just being alive that is a bit out of reach for the rest of us. What I know for sure, however, is that I cherish whatever vision I’ve got left in a way that is only possible as a consequence of what you’ve read about here.

Watching those pigeons was a special thrill and walking out of another eye appointment with an “AOK” from the doc made it one of the best Christmases, ever. I know the anxiety will be back in about five months and accept the inevitability of that as part of the ritual of living with my condition, and that for some others it can be a whole lot more difficult, and I’m grateful for not being them. If that amounts to being “stronger” in some way, I’ll take it, no questions asked.